Read our full interview with Emma Feltes, Joceyln Stacey and Crystal Verhaeghe, co-authors of the 'Dada Nentsen Gha Yatastɨg: Tŝilhqot’in in the Time of COVID' report. We appreciate the time they took to collaborate with us.

What were the key factors that contributed to Tŝilhqot’in Nation’s success in responding to COVID-19?

The most important factor in the pandemic response was the strength of the Tŝilhqot’in people and staff. Many of our interviewees emphasized how well the Nation comes together in times of crisis. The Tŝilhqot’in Nation has significant experience with emergency management, dealing with annual flooding and wildfires, most notably the 2017 wildfires. Since 2017, the Nation has worked hard to become a leader in Indigenous emergency management, through implementing the Nation’s Collaborative Emergency Management Agreement with BC and Canada, the first tri-partite agreement of its kind in the country. The work of building up emergency management capacity and of working with provincial and federal partners before the pandemic proved to be essential in implementing a coordinated, rapid pandemic response. The Tŝilhqot’in Nation has strong relationships with other BC First Nations and leaned on those relationships for sharing resources and for joint advocacy with provincial and federal partners. Finally, the communities rapidly shut down work travel and initiated checkpoints to reduce travel into and out of the communities. This led to the coordination and delivery of supplies and food to the communities to reduce travel to cities and therefore stopping the spread of COVID-19 into households that house multiple generations.

How can teachings from this report help inform responses to other health issues faced by the Tŝilhqot’in Nation?

One positive feature of the pandemic response has been that it brought together health care providers in a way that allowed for knowledge-sharing and mutual support. Many of our interviewees noted that only through the pandemic did they realize the extent to which they had been working in silos. But the pandemic required everyone to adapt to remote work, to be innovative. And as a result, health practitioners and mental health practitioners came together, each meeting weekly to talk through challenges and collaborate on community-based healing. Arts-based projects, virtual writing groups, and photo contests lifted community morale and connection. After a while, community members took the reins, initiating more wellness programs, such as peer counselling groups and traditional healing. Other successes have been found in getting out on the land, and connecting youth with Elders, for example through medicine picking in the summer of 2020. Several interviewees noted equine therapy as an essential program through the pandemic.

The pandemic has amplified existing health crises experienced in Indigenous communities – for example, addiction, mental health challenges, and family violence have all been exacerbated by the stressors of the pandemic. But at the same time, remote work and physical distancing mean that the full extent of these challenges remains out of sight. These compounding health challenges reveal the need for comprehensive health and social strategy for the nation, along with comprehensive supports from provincial and federal partners. In addition, Indigenous Peoples are highly vulnerable to illness and social impacts, as they are likely to have higher incidences of underlying health conditions, overcrowding in houses that are not up to standard, and lack of access to internet, hardware and software which reduced communication and learnability for youth. The health issues noted in the report are not exhaustive, but highlight issues that have been long identified and now only require stronger dedicated attention to properly be addressed. Dada Nentsen Gha Yatastɨg: Tŝilhqot’in in the Time of COVID calls for this level of dedicated support as part of an equitable recovery from the pandemic.

The report is prefaced by a forward by Tl’etinqox Elder Angelina Stump discussing the important connections between disrupting nature and COVID-19. How does climate change connect to COVID-19, and how will the Tŝilhqot’in Nation’s response to COVID-19 inform responses to future disasters?

Pandemics and climate change are absolutely connected. Climate science has long predicted increased disease transmission as a result of a warming climate. They are also connected in the sense that they are both products of colonization. In a broad sense, the Tŝilhqot’in Nation’s response to the 2017 wildfires and to the pandemic is the response to both of these global challenges: Indigenous self-determination.

Cumulative impacts from industry further affect traditional use on the land. Industry and climate change reduce access to lands and further put stressors on wildlife, fish stocks, and traditional plants and medicines. Any impacts to lands impact the social, emotional, physical and spiritual well-being of Indigenous People. Elder Stump highlighted that traditional and cultural practices are determinants of health.

Though the Tŝilhqot’in Nation’s response to COVID-19 was incredibly effective, it was impeded by some jurisdictional challenges. In the future, how can these barriers be eliminated?

The report highlights how important progress is being made through the advocacy of Indigenous nations and the openness of federal and provincial partners to change. For instance, pandemic emergency funding for Indigenous communities from Indigenous Services Canada—though limited—was an improvement compared to the funding model that the Nation confronted in the 2017 wildfires, which required line-by-line approval and reimbursement. Similarly, through the pandemic, the Province has adapted funding policies and has worked toward partial data sharing agreements with the Tŝilhqot’in and other BC First Nations. The challenge is that all of these changes take significant time, resources and effort on the part of Indigenous nations who have to continually educate and advocate. And that always comes at a cost because those same human resources could be spent addressing the direct needs of community members. The fundamental change that needs to be made is that all provincial and federal laws, policies and practices have to be premised on the commitment to self-determination and the trust that Indigenous leaders know what their people need.

This report is about – and for – all First Nations women and girls living in BC. It focuses on their health and wellness, including teachings that First Nations have known since time immemorial contribute to mental, emotional, physical and spiritual well-being at every phase of life – from conception to old age.

This report is part of the Office of the Chief Medical Office’s and the Office of the Provincial Health Office’s commitment to ensure that First Nations people’s right to health and wellness is recognized and protected on an equitable basis. Grounded in First Nations teachings, it uses a strengths-based approach to focus on wellness and resilience – while also applying two-eyed seeing to bring together First Nations and Western ways of knowing. We encourage you to read or download the full report or individual sections here.

RHSRNbc is grateful and humbled to have the opportunity to interview Dr. Shannon McDonald, Acting Chief Medical Officer at the First Nations Health Authority and report co-lead, to provide additional commentary on the rigorous report.

What role do Indigenous women and girls play in enhancing community resilience?

Indigenous women are life-givers, care-providers, nurturers, knowledge holders and teachers. They have held firm but flexible against the misogynist and patriarchal forces thrust upon them through colonization, and have held strongly to the knowledge, medicines and ceremonial roles they have experienced in their lives, and have learned in their communities.

Indigenous women have adapted to modern lifeways that may include multi-generational supports for children or single parenthood. They have remained committed to the transmission of the Indigenous languages and arts, and are a voice for their people. They are statistically more highly educated in Western systems than many of their male counterparts and have increasingly played powerful leadership roles, in governance, academia and business. In childhood, youth, adulthood and as mature women and Elders, they are a force to be reckoned with.

In what ways has the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the strengths and resilience of Indigenous women and girls?

The majority of healthcare providers in First Nations communities are women, and through their clinical and leadership roles have worked incredibly hard to protect the health of their families and communities.

As role models, parents and grandparents, they have supported their families and communities through challenging circumstances – through the many limitations that COVID presented, and sacrificed many aspects of their own lives to do it. Be it food security issues, vaccine implementation planning, testing and contact tracing, formal and informal communications on the subject of staying well in the face of a pandemic, or communicating the unique challenges of life in a First Nations community – the women were there and powerfully advocated for those needs to be met.

How have climate change and ecosystem disruption impacted First Nations' connection to the land, water, and territory?

This is a question the FNHA is actively pursuing the answers to. Through a recent research study – “We walk together” – we are asking youth and Elders in First Nations communities what the connection to the land means for them. We talk about food sources – the nutritional and cultural importance of salmon for example or the challenges to hunt for meat when the environment the animal live in has been lost to development. The discussion often turns to the importance of water, and the evidence that climate change is affecting both the availability and the quality of the water we need to live. Elders speak of the challenges to locate plant medicines when the environment has changed. Heat and wind have created devastating forest fires that have impacted all of these things. People value the life on the land, and the gifts it carries. They mourn the losses and struggle to protect what is left.

How do rural-urban disparities further exacerbate the already disproportionate barriers that Indigenous women and girls face in accessing and receiving quality health care?

The challenges are the same in different proportions – equitable and reasonable access to high-quality care in a culturally safe environment. Primary care for all ages, abilities, gender identities and economic statuses is key. In the face of systemic and interpersonal racism, and preponderance of urban-focused acute care services – the onus for REAL change is on the systems and those who control and unequally benefit from them.

From the report, it is clear significant work is still necessary to eliminate and transform the colonial and racist foundations of systems at the root of these injustices. What are the next steps/ main calls to action?

We specifically did not list recommendations or actions needed. It has been done many times before – brilliant people have come together and written countless strong, specific recommendations – the ‘In Plain Sight Report’, the ‘Truth and Reconciliation Commission's report, the report on MMIW, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People, and many more. The next important step is to LISTEN, to be reflective and honest about the system that was created to advantage some and not others, and to be willing to be part of the change.

(Why do we have to wait until we find small human remains to believe the atrocity that was residential schools – it is time to BELIEVE and move forward.)

Lauren Airth is a Registered Nurse who recently completed her Master of Science in Nursing. She began working in the mental health field as a care aide in 2009 and has focused her entire nursing career in this area. Presently, Lauren works in three different mental health acute care areas at Kelowna General Hospital and is a campus health specialist with the Voice and a clinical assistant with the School of Nursing at UBC Okanagan. For her thesis, Lauren conducted a photovoice study exploring the experiences of older adults with mental health concerns living in a rural area. This research was conducted in the southern interior of BC.

"Photovoice allowed me to explore creative, unspoken elements of participants’ lives and analyze them in a meaningful way. This method of data collection also emphasized the experience of the participant, a key part of patient-oriented research."

Understanding Mental Health Experiences of Adults 50 Years and Older Living in the Similkameen: A Qualitative Study Using Photovoice

Tell us more about your project! Who was the focus of it and why is the topic important to explore?

This photovoice project was conducted as part of my thesis work in the Master of Science in Nursing program at UBC Okanagan. My research explored the experiences of adults aged 50 and over living with a mental health concern in a rural community in British Columbia. This topic is important for many reasons. Mental health concerns are currently the leading cause of disability internationally (World Health Organization, 2014). This statistic aligns with the present mental health landscape in Canada. As the country’s population ages, adults aged 50 and over are expected to have the most mental health concerns of all age groups in Canada in the coming years (Smetanin et al., 2011). The population of older adults is also increasing in size in rural areas (Moazzami, 2015). Despite this growth, there is a paucity of literature regarding the experiences of older adults with mental health concerns in rural communities.

What is photovoice?

Photovoice was developed by Wang and Burris in 1997. It is a qualitative data collection method which aims to help participants “identify, represent and enhance their community” (Wang, 1999, p. 185). This involves providing participants with a camera and having them take photos of what represents the topic being explored – in this case, participants took photos of what represented their life as an older adult with a mental health concern in their rural community. Participants took as many photos as they desired (we recommended no more than 100). They then narrowed it down to about 10 of their most significant photos to explore in individual interviews with myself. Interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide based on the SHOWeD method (Wang& Redwood-Jones, 2001). These interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, then analyzed alongside the selected photos to identify common themes. Themes were finalized in discussion with participants in a member-checking meeting.

What made you decide to use photovoice for this project?

When I first heard about photovoice, it seemed like the perfect combination of science and art. Photovoice allowed me to explore creative, unspoken elements of participants’ lives and analyze them in a meaningful way. This method of data collection also emphasized the experience of the participant, a key part of patient-oriented research. My research used critical social theory and interpretive description, and photovoice aligned well with this methodological structure. It was important to me that the findings would be true to participants’ experiences, and that the process, as much as possible, would be controlled by participants, which photovoice supported. Using photovoice also provided a unique way of presenting results, which helped involve the community and drew in a different audience than typical research journals might.

What are some of the insights (key themes) that emerged from this project? Is there any new knowledge gain from this project that may serve to inform policy and/or practice?

Five key themes arose from the data. For the first theme, mental wellbeing, participants unveiled eight facets of wellbeing: personal qualities, hope, spirituality and gratitude, nature, routine and productivity, medication, substance use, family, and isolation. For the second theme, losses, participants described how they were affected by the loss of abilities, friends, family, lifestyles, and thoughts regarding death. The third theme, stigma, was experienced internally and publicly. The fourth theme was services and supports. Participants identified barriers to support, as well as negative and positive experiences when they accessed services, and the importance of informal supports. Finally, participants’ mental health was influenced by their environment (home, finances, community).

These themes existed in tension with one another. While participants had ways of caring for their wellbeing, these strategies were inhibited by stigma. Stigma was the underlying factor for many of the complexities uncovered. Isolation, poverty, and access to services were all related to stigmatizing experiences. The topic of isolation revealed some interesting dynamics – participants valued intentional solitude but struggled with feelings of loneliness. This relates to the challenges our participants faced when trying to maintain social relationships. Although participants felt they had some negative relationships in their life, they chose to maintain them out of the need for social interaction. There is little literature on this dynamic of older adults’ friendships. Additionally, participants’ personal histories often influenced their coping strategies, and their ability to reflect on their mental health needs.

Themes informed recommendations made for policy development, education, health services delivery, and future research. Specifically, there is a need for more specialized care providers in rural areas to address older adults’ mental health. This need could be addressed by incorporating education on this topic into the curricula of various health and social development programs. It would also be beneficial to see health care workers support the development of peer support groups in rural areas. These groups could incorporate elements of mental wellbeing discussed in this study.

What are some of the outputs of this project (e.g., community exhibition, media release, book publication)?

This project resulted in two major knowledge translation activities, which were decided upon in collaboration with participants. One activity was a gallery event in the community where the research was conducted. Photos from the study were showcased at the community center for a month. Each photo was accompanied by a write-up explaining the themes. The second activity was the creation of postcards. These postcards used photos from the study and featured paraphrased topics from interviews. Postcards also featured a link to a blog where people could see more photos and read more about the study. Some postcards listed local mental health resources for older adults. Throughout my time in graduate school, I presented on this research at three different events (two conferences, one webinar). For the future, I am hoping to publish articles related to my thesis work, to host a photo installation in Kelowna, and I am working on collaborating with the School of Nursing at UBC Okanagan to incorporate aspects of this research into the curriculum.

What did the process look like for engaging community members in the research process?

This photovoice project was made possible through the work of the research team. This team consisted of a patient population representative, a local nurse, a retired registered psychiatric nurse running outreach programs in the area, and my two supervisors. Additionally, this study was funded by Mitacs and the South Okanagan and Similkameen Mental Wellness Centre, and my work was assisted by a scholarship I received from the Canadian Nurses Foundation. We began the study with a photovoice education session, which led into the photo-taking period, and this was followed by individual interviews and the member checking meetings. The initial meeting helped to build rapport, introduce participants to the study, and gave them the opportunity to practice using the cameras we supplied them with. It was important to provide information on the study in multiple ways – visuals, discussion, and typed pamphlets – and be available for questions participants had during the photo taking process.

It was challenging to engage community members due to the sensitive topic our research focused on. Many people feared having their mental health diagnosis exposed, because of stigma. This resulted in two cohorts of four participants. It was important for me to maintain relationship with participants, especially with the length of time between cohorts (one started in July 2018, the other in October 2018) and their different meetings. Relationships were maintained through regular phone calls and allowing myself to become more invested in participants’ lives than I was used to as an RN in acute care.

What was the community response to the Photovoice project? Was there reception to participation?

The community was supportive of our work – the local grocery store contributed food and beverages for the opening day of our gallery event, and the community space was provided to us at a very low cost. Local groups who used the community center also came through to view and discuss the photo exhibit. Many community members who came to see the exhibit commented on the importance of the topic, and how engaging they found the photos. The opening event did not draw in as many community members as we expected, but the people who visited the photo installation appeared very invested. The photo exhibit was available for the public to view for approximately one month.

What are some of the challenges you faced with conducting this photovoice project? What is needed to be successful in conducting a photovoice project?

The biggest challenge was recruitment. In rural communities, people feel much more visible, and participants feared their mental health concerns would be exposed. Successful recruitment was largely thanks to the positive rapport workers in the community had with their clients. Another challenge was the type of cameras we used (we provided participants with point and shoot digital cameras); the cameras were difficult to use with certain physical concerns (ex. tremors, arthritis). Given the nature of the study, participants also found their mental health prevented them from being able to take all the pictures they hoped to. It is important to create a safe space for participants to express their concerns and feel heard, and to leave as much control as possible in the participants’ hands. I believe patient-oriented research is the key to a successful research project and creating findings that will be of benefit (e.g., raise awareness, reduce stigma, and provide input for health services delivery change).

If you could do this type of project again, what would you do differently?

Regarding recruitment, I would speak with community leaders personally. This would include reaching out to leaders in historically marginalized populations to improve inclusiveness of the participants in the project. Recruitment may have been more successful if I could have met in person rather than over the phone with each interested individual prior to the start of the study. I would also have patient population representatives more involved in the recruitment piece, as they are more connected in the community and understand the community’s culture. I would try to shorten the meetings as well, since some participants became tired or found it difficult to commit so much time to the larger group meetings. Regarding the cameras, I would use cameras that are more accessible (ex. larger buttons, steadier focus).

Overall, what did you like most/least about facilitating this Photovoice project?

It was an honour being allowed into participants lives and coming to understand what it is like to be an older adult in a rural community with a mental health concern. It was an enjoyable challenge to use photography and interviews to answer a research question; photovoice uncovered elements of participants’ lives that I never would have thought to ask about, such as their time spent in nature. The most difficult part of the project was recruiting enough participants, and ensuring each participant grasped the purposes of the study. I had to establish the difference between exploring this topic as a researcher, while also being an RN who works in mental health. This also meant using previous photovoice studies to explain to participants how their photography was being used as part of a research study.

To follow and learn more about this project, more content will be made available throughout their website at: https://blogs.ubc.ca/ruralmentalhealthstories/

References

- Moazzami, B. (2015). Strengthening rural Canada: Fewer & older: The population and demographic dilemma in rural British Columbia [pdf]. Retrieved 11/17 from http://strengtheningruralcanada.ca/file/Fewer-Older-The-Population-and-Demographic-Dilemma-in-Rural-British-Columbia1.pdf

- Smetanin, P., Stiff, D., Briante, C., Adair, C.E., Ahmad, S., & Khan, M. (2011). The life and economic impact of major mental illnesses in Canada: 2011 to 2041 [pdf]. Retrieved 10/17 from http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/MHCC_Report_Base_Case_FINAL_ENG_0_0.pdf

- Wang, C.C. (1999). Photovoice: a participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health, 8, 185-92. Retrieved 08/17 from https://home.liebertpub.com/publications/journal-of-womens-health/42

- Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education and Behavior, 24, 369-387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309

- Wang, C. C., & Redwood-Jones, Y. A. (2001). Photovoice ethics: Perspectives from Flint photovoice. Health Education and Behavior, 28, 560-572. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810102800504

- World Health Organization (2014). Mental health: A state of well-being. Retrieved 11/17 from http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/#

Bonnie Fournier PhD, MSc, BSN, RN

"My clinical practice experience has focused on community health, mental health, and global health. I am a population health researcher with an interest in the intersections of place-people-health-policy and particularly in novel approaches and interventions to improve health outcomes with a focus on integrated knowledge translation strategies. I am interested in building resilient communities in order to mitigate the effects of climate change events on mental health. Currently, I am undertaking research with youth to understand youth engagement in health system planning using arts-based methods in rural communities." - TRU (Learn more here)

Tell us more about your project!

The two-year SSHRC funded project working with youth aged 14-18 in Ashcroft and Kimberley, BC. The hope is to gain a better understanding what it is like to be youth living in a rural community through youth engagement using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach and arts-based methods such as photovoice. CPBR engages youth in all aspects of the research process can facilitate youth to gain greater control over their lives, take a proactive approach in their communities, and develop critical understandings of their sociopolitical environments. Understanding the challenges, barriers, and strengths of youth through art, also provides a platform for youth to find solutions and take action to strengthen their lives and improve their community. However, youth are rarely asked to participate in decision making around services and programs that affect their lives, and often their involvement remains marginal and tokenistic. When engaged in meaningful decision-making – in schools, youth organizations, and communities there are positive development benefits for youth. We are interested in know more about what it is like to be a youth living in a rural community and how to strengthen their lives.

What is photovoice?

Photovoice is a method that provides cameras to individuals to take pictures of their lives. In our project, youth are taking pictures of issues, concerns, or challenges they have in their lives or in their community. They bring their pictures and write a story about why they took the photo, what it means to them, how it relates to their lives and if it is an issue or concern, why it is happening and what they can do about it. An art exhibition of their photos will likely be one of the outputs of the project, providing youth with a forum to showcase photos and talk with others about their lives and how being part of the CBPR study increased their positive youth development.

What made you decide to use photovoice for this project?

Photovoice is a powerful way to tell stories. I have used this method many times in previous projects and have seen the strength of using a photograph to share a story about something important to that person. Youth in the project write a reflective piece for each photograph using the acronym SHOWeD :

- What do you See here?

- What is really Happening here?

- How does this relate to Our lives?

- Why does this condition Exist?

- What can we Do about it?

What are some of the insights (key themes) that emerged from this project? Is there any new knowledge gain from this project that may serve to inform policy and/or practice?

Youth want time and space to talk about what is important to them without having to be told what to talk about. Both community youth groups have formed a bond with each other, supporting and encouraging one another in their lives. Photovoice is a good method to engage youth in research. It is fun and gives them a purpose to meet and discuss their photos and stories. Youth think deeply about social issues which has led both groups to discuss climate change and the impact on their mental health.

What are some of the outputs of this project (e.g., community exhibition, media release,book publication)?

Photovoice is just one of the methods in this project. The youth are also using other art forms to express themselves. Some youth have sketched or painted about an issue in their community, music and theatre are also being explored for expression but also to create change in their community.

What was the community response to the Photovoice project?

Was there reception to participation? We are still in the middle of the project but response from both community schools has been positive. One school is providing space for the participants to meet.

What are some of the challenges you faced with conducting this photovoice project?

Finding digital camera’s that people are willing to donate. Using phone cameras can be an issue with confidentiality and easy access to social media where pictures can accidently be uploaded. So we are using digital cameras. However, we were only able to have a few donated to the project.

What is needed to be successful in conducting a photovoice project?

Training in the photovoice method and having access to good digital cameras.

If you could do this type of project again, what would you do differently?

Because both communities are rural, there are issues with transportation for the youth to come to meetings and for the PI’s to also access the communities due to distance. We have been using BlueJeans – an online video streaming program so that we can all connect and have also connected both groups of youth in each community with each other to share their pictures. This has been the most interesting learning for both the youth and the researchers. Youth are learning from youth in another rural community what it is like to live in their respective communities.

Overall, what did you like most/least about facilitating this Photovoice project?

We are still not done. We have another year to go. Its been great to see the youth become interested in their communities and wanting to change things and then watching them take action- one group is currently working on a song/video about having more green space in their community for youth and will present it to the major and council.

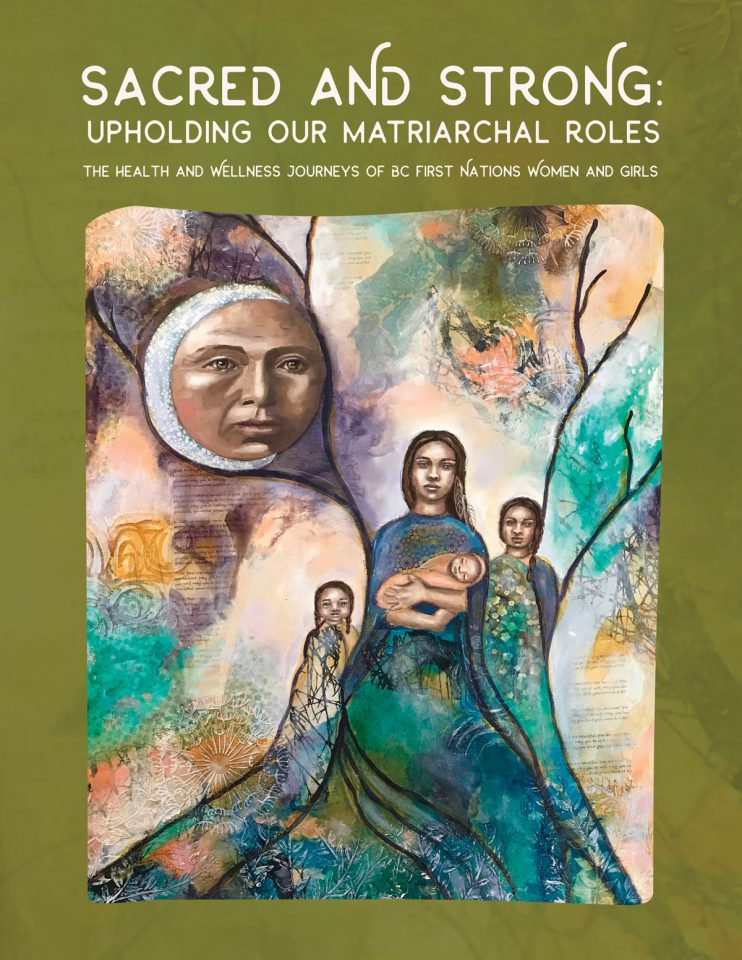

With permission I am sharing two photographs and their stories from the project!

Water under the bridge

I want to clean up the area. There are homeless people that go there and leave their things like blankets and litter. There is also a pub and restaurant nearby that produce a lot of litter that isn’t cleaned up. There are community groups that clean up garbage although they often don't clean up under the bridge because it isn't a common spot that people look at, so they focus more on the parks. There is some broken concrete sitting under the bridge from some sort of walkway that broke and never cleaned up. Maybe with more affordable living there would be less homeless people living there and leaving garbage. I used to go there in the summer to hang out with his friends and swim and thought it was a good spot but now the bank has widened out and become dirtier and full of garbage. Often there are people hanging out there that make it feel unsafe.

Mental Health

This photo represents how mental health can be affected when you aren't prioritizing or taking care of your own needs. School is known for stressing out students, and I don't think mental health is always being addressed in school. Being busy isn't always a bad thing, but prioritizing only school or work rather than self care eventually takes a toll on mental health. I think if being able to balance things like school and self care were addressed more, students would have an easier time managing stress.

Dr Woollard completed two terms as Head of the Department of Family Practice, Faculty of Medicine at the University of British Columbia. He has chaired senior committees, councils and task forces for the BCMA CMA and CFPC in the areas of medical education, environmental health and ethical relations with industry. He was CoPI on a large IDRC grant developing a community of practice in ecosystems health and has provided leadership in a number of major initiatives grant-funded through the Science Council of British Columbia, the Tri Council Research Fund, CIHR and a Major Collaborative Research Initiative with SSHRC. He works extensively in the issue of the social accountability of medical schools and is currently actively involved in a national medical school founded on these principles in Nepal—a school based on a feasibility study he conducted in 2004. He is also working in East Africa on social accountability, primary care and accreditation systems. He has completed a five-year, five-university project on localized poverty reduction in rural Vietnam.

He has chaired senior committees, councils and task forces for the BC Medical Association, Canadian Medical Association and the College of Family Physicians of Canada in the areas of medical education, environmental health and ethical relations with industry. His primary research focus is the study of complex adaptive systems as they apply to the intersection between human and environmental health.” – Linkedin (more here: https://ca.linkedin.com/in/bob-woollard-b75b8a2b)

Thank you Dr. Woollard for joining us on this interview! We are really excited to have you share your experiences in rural health research. Could you tell us a little bit about yourself?

My name is Bob Woollard and I am a physician and a professor in Family Medicine at the University of British Columbia. I have been affiliated with RCCbc since its inception. I was a country doctor for 20 years before I came to the University, first in a small town in the prairies and then in Clearwater BC where I had practiced for 16 years. I was Department Head of Family Practice for two terms at UBC. When I finished my second term as Department Head at UBC, I focused a lot of my own work on rural issues at RCCbc. In addition I have been involved in issues of rural health services, ecosystem health and social accountability/justice in various parts of the world. That has been a central focus in my career and it is gratifying to see the evolving role of rural medicine in helping us to understand population health.

What current research projects are you working on?

I am working on a wide range of projects primarily on social accountability in medical schools. In particular, their accountabilities to rural communities. In addition, I am involved in a four university interprofessional and engaged project using watershed as the unit of analysis and looking at the health and environmental effects of resource extraction—specifically on the health of rural women and children. I am also co-chairing a global consensus initiative on social accountability and accreditation—to a great extent a follow through of the Global Consensus on Social Accountability (GCSA) and the 2017 World Summit on Social Accountability that I co-chaired in Tunisia. Several other smaller initiatives also fill my days—and my heart.

What are some upcoming global health projects related to rural medicine that you will be involved in these next few months?

In terms of global health, one I can think of is a specific project which has been the development (and evolution) of a national, public medical school located in Nepal where I did the initial feasibility study in 2004. Its focus is on rural and lower caste health. I have been closely involved with this project in terms of it coming into being and we have our third full class of graduates practicing in rural areas in Nepal. It has been a work of love from conception to execution.

Next week, I will be hosting the founding vice chancellor of that medical school who has been asked to establish a university. Its focus will be on the development for folks interested in providing public service through the reflection of values such as capacity building, developing the right skills and attitudes to ensure Nepal is able to steer towards an effective future.

Some of my previous global health projects occurred in East Africa and Indonesia. In Canada, I chaired the accreditation systems for medical schools both in undergraduate and professional development. One of the major projects I am working on now indirectly linked to global health is an appreciative inquiry on how social accountability has been adapted and expressed in medical schools here in Canada. There will be publications of that research in the next few months. At a global level, I have been co-chairing with Charles Boelen an initiative to develop a consensus paper on the role of accreditation in advancing social accountability.

In 2010, Charles and I co-hosted a Global Consensus on accountability in South Africa in efforts to describe and reach a global consensus from all regions of the World Health Organizations on what a social accountable medical school should look like. In 2017, we co-hosted a World Summit in Tunisia to develop an action plan to move forward in animating social accountability. In each of those places that I have worked, teams collaboratively try to establish a consensus on the basis of research methodology such as using a Delphi process for the global consensus to erect the best evidence towards the formation of these joint efforts.

The inequitable health status of rural is pretty universal. Since the principles of social accountability apply not only in medical schools (and other professional schools), there is also a responsibility to focus their attention on the health needs of the population they serve who are at negative variance in the health status of the dominant or majority of the population. When I did my initial studies in Nepal, for example, there was a 20 year difference in life expectancy in populations residing in the Katmandu Valley and the rest of Nepal. As the Prime Minister at the time indicated to me, if we do not fix that, a Civil War (which had just ended) would resume. In British Columbia, there is a two year difference in life expectancy which is equally unacceptable. The evolution of social accountability at so many different levels has required research methodologies to help give direction and rural is central to that.

What inspired your interest in rural health research?

What animated me was that I grew up in ‘the bush’ in west of Edmonton where my graduation class was about twelve people. I married a wonderful woman who grew up in a small town in South Carolina and when we decided we were going to have children, we went into a rural area to raise them and to practice. That has worked out very well. We lived in rural for about 17 years before we moved to the university. At the rural scale, you are able to study complex systems of care much easier than an complex urban setting. The RCCbc ethos (and also where my focus has been) is that urban has much to learn from rural. If I can be said to have an organized, academic philosophy, it would related to complex adaptive systems. And so that is a theory in which a rural scale is embedded and more accessible to study.

You made a comment on how urban has much to learn from rural, do you think rural health specifically in the local context of BC and Canada has much to learn from global health through collaboration and engagement with the international community?

The short answer to that question is yes. Global health looks at the global causes of these health disparities and tries to address them. Partly just by virtue of the fact where many (if not most) lower/middle income countries are primarily rural. And to me, where the interest lies is in reciprocal learning. Because we have consistently disadvantaged rural. There is a ‘hidden curriculum’ that has been well studied that has built prejudice and marginalizes of rural as a desirable place to learn, live and practice. On the other hand, there are other countries where development of primary care that valorizes rural care and supports it have been successful.

I have had the privilege to work in global health projects in places like Nepal, Vietnam, Indonesia and Uganda in developing the rural education portion of the curriculum there. All of this to me is a natural connection between the global concerns and local impact on policy decisions. One of my projects that received a large grant earlier from CIDA (https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/members_partners/member_list/cida/en/) was working on poverty reduction in Vietnam. The five year project involved six universities in which two were Canadian (one was UBC). I learned a tremendous amount there that directly influenced the Northern Medical Program here. As we did the engagement process in Vietnam, I was asked by the Dean to be involved in the development of the Northern Medical Program and as Department Head, I helped develop the post graduate program and encouraged the undergraduate program in the North that was informed by the experiences I had in Vietnam.

Another thing I will be doing at the end of this month is doing field work in New Brunswick. One of the first large grants I got after finishing my term as a Department head in 2008 was the million dollar grant looking at collaborations at UNBC, University of Guelph, and an entity at Universite de Quebec a Montreal called Symbios where there is an ecosystem approach to health. We developed a full community of practice that has now matured into a very active collaboration with nine universities. It is multidisciplinary, focused on equity, and other characteristics to address the fact that rural, resource-dependent (particularly aboriginal women who reside in these areas) communities are placed with increasing environmental and social marginalization and risks.

Do you have any tips for new researchers who are new to conducting research?

To get into research, it is important to understand what science is for and what it is. I think we humans are born curious. If we are able to not only maintain but refine our curiosity, we will serve our society best. Research at its base is “organized curiosity”. The assumption that policymakers or others may have is that science gives us truth. In fact, it took a playwright to remind us; "The aim of science is not to open the door to infinite wisdom, but to set a limit to infinite error.” -Bertolt Brecht in The Life of Galileo (1939)

So the function of science is to be organized in your curiosity and that is a different stance than that thrown at us in high school and university—in fact the answers aren’t in the back of the book—or under a rock. Be curious. Because to develop your career in research requires developing the skills of organized curiosity that allow you to disprove hypothesis or test them to the point where stakeholders such as a policymaker who is looking for advice or an institution that wants direction in its priorities can be informed which directions might be most promising, through rigorous findings in research.

As you move down the path (i.e., ‘you’ as in society and ‘we’ as in the scientific community), there will be a need to work together to understand whether we are achieving what we thought we were going to achieve. Using research to address inherent skepticism rather than assuming it to be a truth seeker will help us challenge how we build the future of our society.

Thank you again Dr. Woollard for sharing with us your experience working in rural health on both a national and international scale. We look forward to learning more about the ongoing projects you are involved in and watching it develop. I would like to leave this last question for something fun.

If you won the lottery, what is the first thing you would do?

After I had gone to university, I had difficulty deciding what I wanted to pursue where my choices were either Chinese History Philosophy (which I had a scholarship in) or accept my admission to medical school. I had no idea what I wanted do. I was 18 at the time and had to make my decision by noon. I asked a friend who was shooting pool at the time what I should choose. And he said, “Well, if I make this shot, you’re going to medical school. And if I miss it, go take history.” It was decided when he made that shot.

Another little fun fact. I am living on the top story of a three level duplex and my grandson was born on the first level of the duplex. I get up every morning and have my coffee in the room he was born in. So to answer that question, I already won the lottery. From growing up as a poor boy from the bush in Alberta, I had already won the lottery a thousand times over. That is one in many examples of the good fortune I had. It is also an affirmation of how capricious life is. But if you grasp it passionately then, as Dicken’s put in the mouth of Mr Macabar: “Something will turn up”.

"David Snadden is a graduate of the University of Dundee in Scotland and was a full-time rural general practitioner and family resident trainer for 11 years in the Highlands of Scotland. Following further academic training at the University of Western Ontario, where he completed a Master’s degree in Family Medicine in 1991, he returned to Scotland and became Senior Lecturer at the Department of General Practice, University of Dundee. During his time in Dundee he helped develop the first integrated postgraduate and undergraduate Department of General Practice in the UK and also completed his Doctoral degree, his thesis explored the use of learning portfolios in general practice training. He became Director of Postgraduate General Practice Education in 1996 and jointly led the integrated department until 2003. David also worked with the teaching hospital sector as Associate Postgraduate Dean where he was responsible for the first year of general residency training, some specialty programs and fitness to practice issues. He is a Fellow of the Royal College of General Practitioners, a Certificant of the College of Family Physicians of Canada and a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. David joined the Northern Medical Program in July 2003 to lead its establishment and development. The distributed medical education model developed in BC was innovative and helped shape similar changes across Canada and internationally. In 2011 he was appointed as Executive Associate Dean Education in the Faulty of Medicine and was responsible for all the educational programs in the Faculty across the Province until his term finished in June 2016." - UNBC

More about Dr. Snadden here!

Thank you for joining us this month to talk about your work in rural health across the province. How did you come to get involved with RHSRNbc/RCCbc?

As Rural Chair I work closely with the RCCbc.

What research projects are you currently working on?

Currently, I have various projects ongoing but some of my main research projects include:

- The Partnering for Change 2 study: This is a study that is examining the processes of Primary Care Reform in Northern BC. The study is examining the “how” of the reform processes and the partnership between Northern Health, health care staff, including physicians, and communities. Changing health systems is a long process and publications from Partnering for Change 1 are in process, and the current study is just starting and due to run for at least three years.

- Developing a Hermeneutic Approach to Implementation Science: This is a SPOR project and is just starting. Both this and the above study are led by Martha Macleod, Northern Health / UNBC Knowledge Mobilization Chair.

- I am just completing a project with Australian Colleagues which was a review of Australian and international approaches to family medicine residency training there which focuses on informing a reorganization of Australian residency programs.

- I am also a part of the CIHR Funded national Early Career Primary Care Physicians in Canada project led by Ruth Lavergne at SFU.

What inspired your interest in rural health research?

I started off as a rural family physician in the Highlands of Scotland and have always been intrigued by the way rural communities and health professionals deal with the problems they face through innovative solutions.

In your opinion, why is research important in the rural health context?

Rural communities, wherever you go, have poorer access to health care, yet rural health care workers are some of the most highly skilled I have come across. Research in general follows the same pattern where the rural elements are often excluded and consequent research findings do not translate well to rural. Rural has much to offer society in general in terms of how to deliver of health care and also has significant issues to overcome that are not necessarily relevant in urban areas. There are lots of opportunities in rural setting to engage with research and lead research that will help rural health care.

Do you have any tips for members just getting started with research?

The modern research environment is complex and there are certain processes such as gaining ethics approval for any study that must be followed. It is hard to start the research journey alone so look for help such as that provided by the RCCbc or the RHSRNbc to get some tips on how to get going.

What are some important elements to consider when conducting research?

Ethics is important as is funding, as even small studies need some resources. The most important thing is to take advice at the beginning on study design and what you are hoping to achieve and see if there is anyone with research experience you can collaborate with.

What are some of the obstacles you had faced when conducting research and how did you overcoming them?

Research is more fun when in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team. Having people you work with over a period of time is the best way to overcome obstacles like funding and how to effectively design a study. In my early research career I found formal training to be a great help as well as it helped me understand various methods better.

Getting to the fun stuff now, what is your favorite indoor and/or outdoor activity?

I like being in the mountains, whether it is hiking or climbing in summer or backcountry or cross country skiing in the winter.

If you won the lottery, what is the first thing you would do?

I would figure out how to give most of it away – probably through setting up scholarships for underprivileged students to pursue health careers.

If you could go back to any year in time, which one would you choose and why?

Probably the turn of the century when I was more fit and active than I am now, and when the world was a much safer place to travel in.

What is one fun fact about yourself?

For someone who loves rural environments I was born and raised in big cities – Mumbai and Singapore.

Thank you Dr. Snadden for joining us on this month's Spotlight Feature!